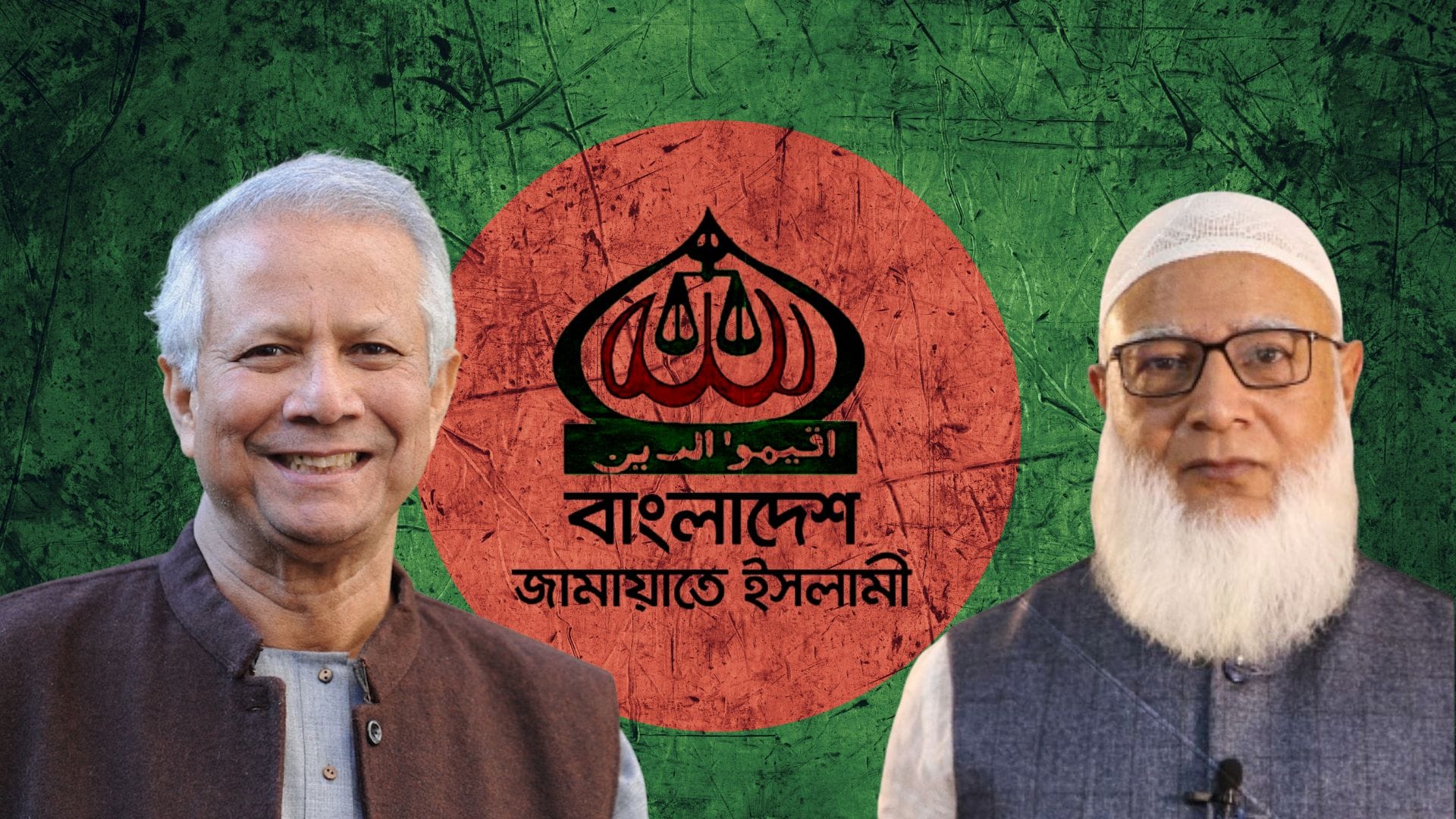

It has been only a short time since Sheikh Hasina’s dramatic ousting from power, toppled by an uprising that followed her government’s decision to use lethal force against protestors. The killings of demonstrators and injuries inflicted on countless others — many at the hands of ruling party workers — left an indelible mark. In the aftermath, Bangladesh now faces a moment of redefinition. With the Awami League in retreat, new contenders are vying for power. Among them, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) is emerging with surprising momentum, drawing grassroots support in a nation where speculatively over 85 percent "identify with Islam".

Who is Jamaat-e-Islami?

At its core, Jamaat is an Islamist political party. Islamism is the belief that Islam is not only a religion but also an inherently fundamentalist political system — that governance itself must be shaped by "divine law" revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and place their definition of "God" and "God's Decree" above all else.

The party’s constitution makes this explicit. It asserts that Allah’s rules govern every sphere of the universe, that mankind is His viceregent on earth, and that Prophet Muhammad’s life and principles represent the sole ideological path for humanity. For Jamaat, the purpose of politics is not merely governance, but establishing a society that prepares individuals for "salvation in the hereafter" which is "life after death".

Yet within this sweeping religious framework, Jamaat makes space for a contradictory pledge to non-Muslims. Its policy on paper guarantees civil rights, equality of opportunity, protection of property and life, and the preservation of the cultural distinctiveness of minority communities. It promises equal pay and state honorariums for priests and ministers of other faiths alongside imams and muezzins.

Society and Religious Life

Jamaat paints a vision of a society rooted in highly subjective "order and morality". In this vision, every Muslim man and woman would be schooled in the teachings of Islam, guided in ritual, and directed toward a more disciplined religious life directly through the education system. Schools and media would no longer be neutral spaces of debate and discourse, but the indoctrination of "spiritual training".

To protect this imagined moral order, Jamaat proposes blasphemy laws — harsh measures to prosecute “anti-religious propaganda” in books, broadcasts, or conversation. Their charter promises “equal religious rights,” yet those very rights would exist alongside sweeping bans on alcohol, gambling, and what they term “unsocial activities.” In Jamaat’s world, freedom is offered with one hand and withdrawn with the other.

In politics, dissent itself would be curbed: strikes, blockades, and mass protests — long a weapon of the powerless in Bangladesh — would be outlawed outright in a bid to "enforce order".

In practice, Jamaat positions itself as both "moral guardian and welfare provider", offering stability to a weary population. Yet its inclusivity is conditional with freedoms tethered on a string. For every promise of equality, there is a clause of restriction; for every vision of "justice", a tightening of control.

It is this tension — between the "rhetoric of fairness" and the reality of enforced conformity — that defines Jamaat’s political project.

The Islamic Welfare State Vision

Perhaps most striking and potentially alluring to Bangladeshi's sitting on the fence is Jamaat’s attempt to blend religious decree with socioeconomic policy. It champions the use of zakat (alms-giving) as an instrument of poverty alleviation and promises training, micro-credit, and industrial expansion to integrate the poor into the workforce. Programmes for female-headed families, the disabled, widows, and the elderly would be expanded along with a proposal for Northern Bangladesh’s monga (extreme poverty) to be addressed with infrastructure, diversification of agriculture, and guaranteed employment schemes.

In a country where decades of mismanagement, nepotism, and elite corruption have corroded trust in secular institutions, Jamaat’s promise of a moral order anchored in "divine legitimacy" strikes a willing chord. For many, trusting in God’s decree feels safer than trusting “weak” human leaders — even if the leaders of Jemaat themselves are, unavoidably, human.

The Bigger Question

Bangladesh is now caught between two visions. On one side, a discredited secular order tainted by dynastic politics, authoritarianism and corruption. On the other, an Islamist movement offering the "clarity of divine law" and the order of religious certainty. Both appeal to a public weary of scandal and betrayal.

But the contradiction remains — if the leaders who promise God’s justice are still just men, will they not carry the same human flaws that have undermined secular governance?

And if divine mandate becomes the basis of politics, where does dissent — the lifeblood of democracy and representation fit in?

Author

News cycles today feel more dehumanising than ever. Netizen's deserve journalist's that believe in the power of narratives to inspire positive change — putting activism before profits and creating a blend of journalism that is raw, human, and alive.

Sign up for The Fineprint newsletters.

Stay up to date with curated collection of our top stories.