Some readers might be wondering how India and Singapore are even connected — the answer is trade. India is one of Singapore’s largest trading partners, and both countries are bound together by the Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA), which aimed to boost investment, business links, and the free movement of professionals across borders.

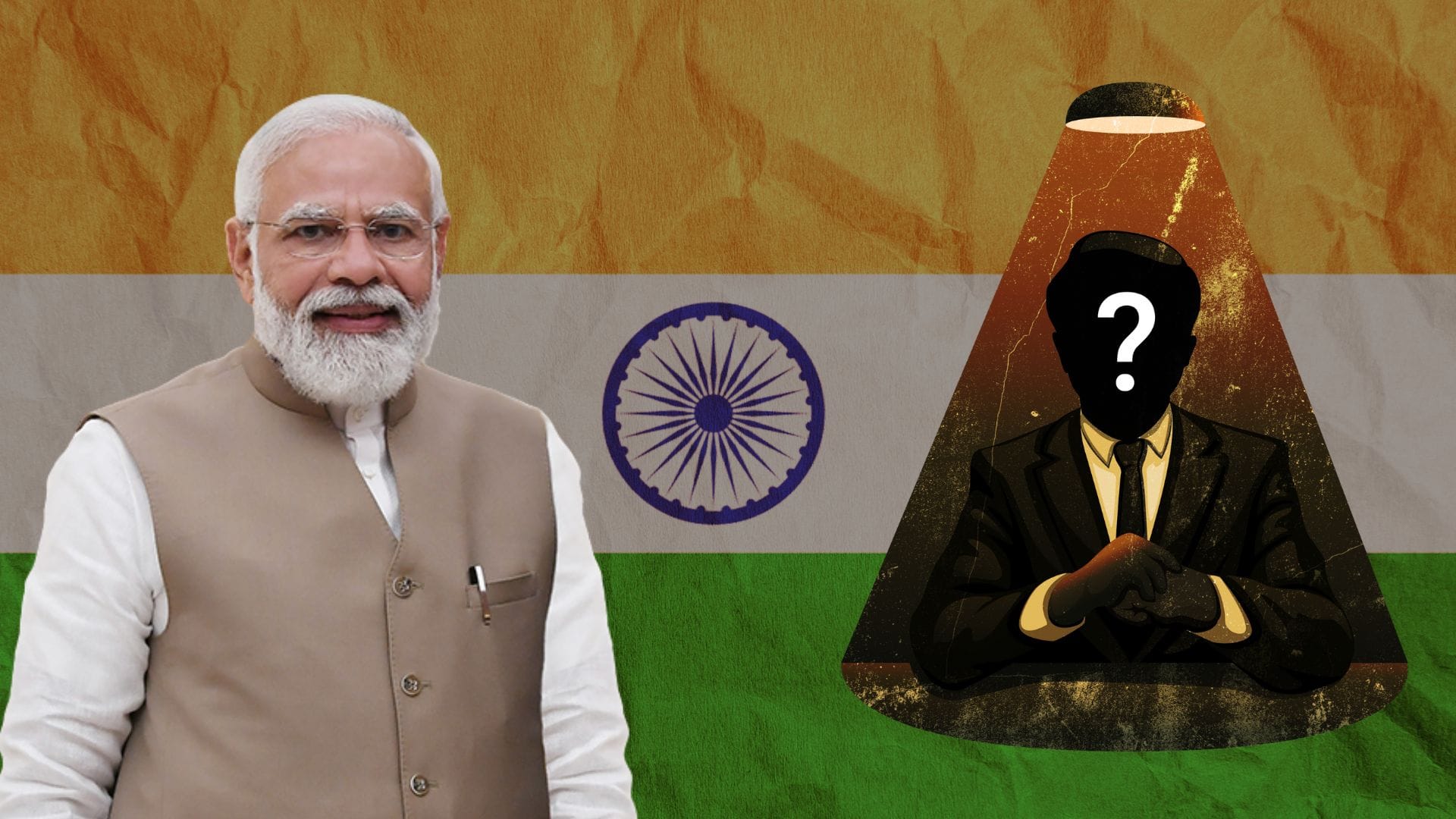

When Narendra Modi swept to power in 2014, he carried the promise of a “new India” — free of corruption, transparent in governance and bold in economic vision. More than a decade later, the two most dramatic financial reforms associated with his government — the 2016 demonetisation and the 2017 electoral bonds scheme — remain among the most contested decisions in modern Indian politics.

Ironically, Both were framed as tools to fight black money and curb corruption. critics argue that the policies have instead entrenched the very problems they promised to solve.

Today, Narendra Modi's government faces allegations from those in the opposition bloc of stealing votes and cronyism.

The Shock of Demonetisation

On the evening of 8 November 2016, Indians watched their Prime Minister announce that ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes which was 86% of the country’s cash supply would cease to be legal tender overnight. The policy, known as notebandi (demonetisation), in theory, aimed to flush out unaccounted wealth, curb counterfeit currency, and push the economy toward digital payments.

What followed in practice was chaos — millions of citizens queued for days outside banks to exchange old notes. Informal economies overwhelmingly dependent on cash like Small businesses, street vendors, and rural workers ground to a halt.

And when it was all over, The Reserve Bank of India later revealed that over 99% of the demonetised notes were returned to the banking system, undermining the claim by the BJP that hoarded black money would be extinguished.

For the wealthy and politically connected, sophisticated channels ensured safe conversions of cash. For daily wage labourers, farmers, and the poor, the policy translated into lost livelihoods as people spent hours queueing at ATMs.

If demonetisation failed to achieve its intended goals, the electoral bonds scheme introduced in 2017 went a step further — it completely rewrote the rules of political donations.

The government claimed many individuals and companies hesitated to fund parties out of fear of political retribution. The "logic" was by keeping donors anonymous to the public, electoral bonds would supposedly encourage more people to donate.

The numbers were staggering. By 2024, minimally,₹11,000 crore had been channelled through electoral bonds, with the ruling BJP receiving the lion’s share. Critics branded the scheme as “legalised corruption” — a system where companies could quietly purchase influence and expect regulatory or policy favours in return.

The Supreme Court Intervenes

In February 2024, India’s Supreme Court struck down the electoral bonds scheme as unconstitutional. The judgment was a long time coming — by shielding the identities of donors, the scheme violated the citizen’s right to information and tilted the playing field in favour of those in power. Transparency, the court held, was essential to democracy.

Taken together, demonetisation and electoral bonds illustrate the paradox of Modi’s anti-corruption crusade. On one hand, notebandi was a direct — and devastating — assault on the cash economy, justified as an attempt to root out shadow money. On the other, electoral bonds quietly opened a new channel for opaque corporate funding at unprecedented scale.

The effects were asymmetric. The poor bore the brunt of demonetisation, while political elites benefited from the influx of untraceable donations. Cash was delegitimised for ordinary citizens; anonymity was legalised for political contributions.

Did The Bharatiya Janata Party “legalise corruption”? Legally, no: bribery remains a crime, graft remains punishable. But by enabling a system where massive, illusive funds could legally flow into party coffers, BJP's government definitely restructured corruption.

Author

News cycles today feel more dehumanising than ever. Netizen's deserve journalist's that believe in the power of narratives to inspire positive change — putting activism before profits and creating a blend of journalism that is raw, human, and alive.

Sign up for The Fineprint newsletters.

Stay up to date with curated collection of our top stories.