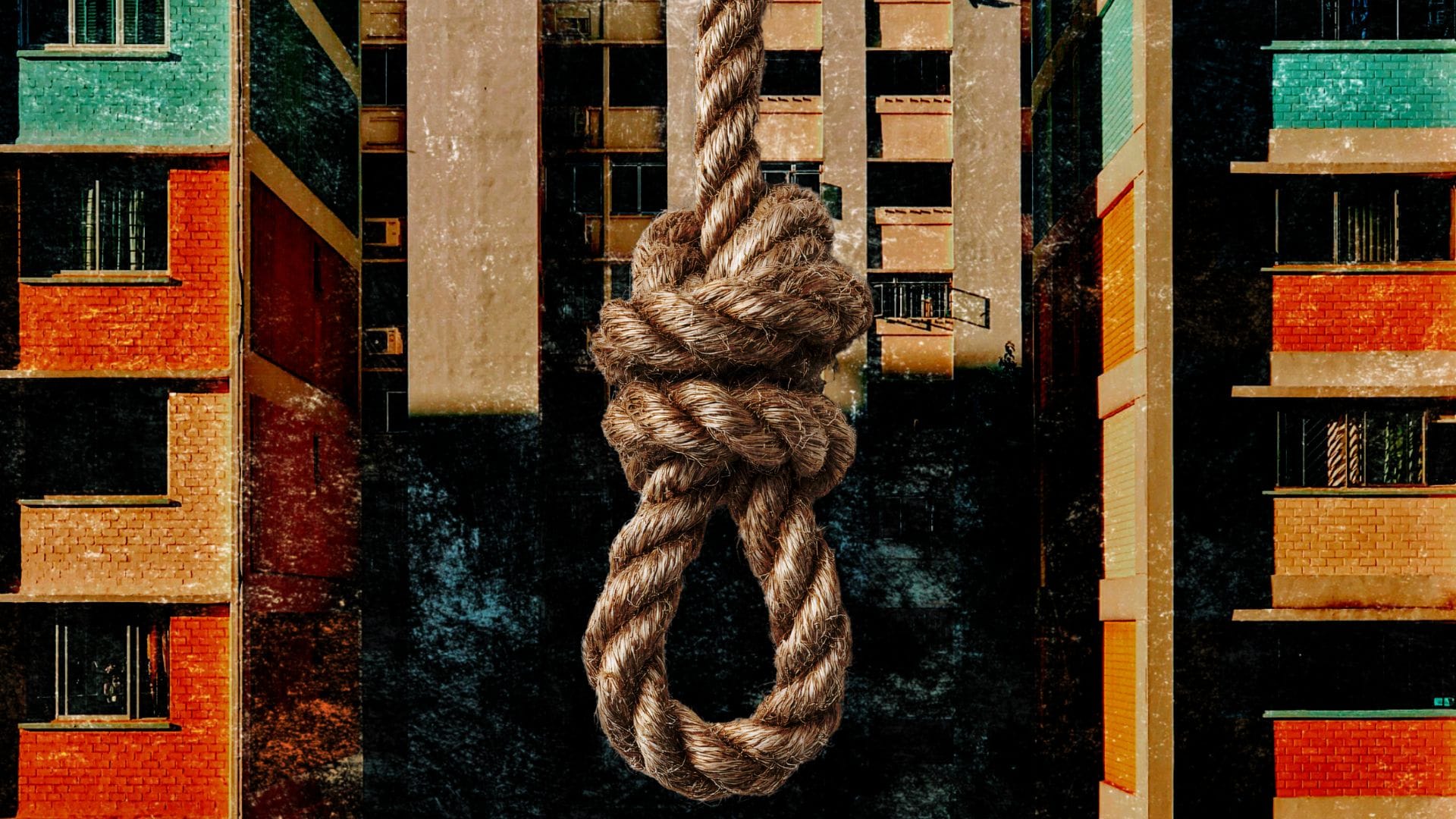

Singapore: It is a reality that many Singaporeans remain startlingly unaware that their Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats, often considered the bedrock of national stability and social mobility, are in fact ticking-time clocks with a 99-year leasehold. At the end of that lease, the property does not belong to them, nor to their children. Instead, it reverts back to the state — critics (including the author) have dubbed this the “99-year death sentence.”

The Illusion of Perpetuity

Many Singaporeans hold onto the belief that, when the end approaches, the government will inevitably offer an en bloc scheme — where blocks are bought back before leases expire, residents compensated, and new flats provided. But this belief is far from guaranteed. The Selective En Bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS), introduced in 1995, applies only under very specific conditions: the site must be economically viable, have redevelopment potential, and fall within the government’s long-term planning vision. To date, less than 5% of HDB flats have benefited from SERS. Many, if not most Singaporeans will simply watch their homes depreciate to zero value as the 99-year clock winds down.

World-Class or Silent Noose?

Globally, Singapore’s public housing policy is lauded as a success story. Over 80% of citizens live in HDB flats, and home "ownership" rates surpass those in most developed countries. Foreign observers point to gleaming new towns, accessible mortgages, and subsidies that allowed working-class families to climb out of "poverty" within one generation.

In almost every social democratic nation home-ownership "that is true ownership and not a lease" has become the fundamental bedrock of society and good policy — prominent examples include Finland, Norway, Sweden and Australia (although they are currently experiencing housing shortage following a widely criticised immigration boom).

But the Singaporean policy, when examined through the long arc of time, reveals a quiet spectacle — Unlike freehold properties — where titles can be passed down indefinitely — HDB leaseholds ensure each new generation begins afresh. Parents cannot leave their flats as true inheritance; children inherit only a diminishing lease, often with far lower market value. For the middle class and working poor, this strips away the chance of accumulating intergenerational wealth, even as the wealthy continue to grow their legacies through freehold estates.

The Growing Divide

This system entrenches a subtle but growing divide. Families that can afford freehold properties enjoy the luxury of passing wealth seamlessly across generations. Their children start life on a higher rung of the wealth ladder, benefiting from assets that not only appreciate but also endure. In contrast, HDB dwellers — the majority — depend on state-subsidised schemes such as the Lease Buyback Programme (selling part of the remaining lease back to the government to fund retirement), or CPF housing grants among other subsidies that cushion but do not erase the cycle of state-dependency.

The promise of home ownership is not quite what it seems. It is, rather, a long-term rental with the appearance of permanence, masked by decades of public trust in government planning.

Why Aren’t Singaporeans Outraged?

if the arrangement is indeed "one-sided", why do Singaporeans not see it as unfair? Some reasons stand out:

- Trust in the State — Singapore’s political culture prizes competence. Citizens often assume that when leases run low, new policies will be created, or that future governments will not allow mass homelessness.

- Cultural Short-Termism — With leases stretching across nearly 2 generations, the end feels distant. Many are willing to let their grandchildren deal with the consequences rather than confront the structural issue today.

- Subsidy Dependency — Rebates, grants, and upgrading programmes provide recurring relief, reducing immediate dissatisfaction. In turn, this keeps public opinion placated, even as the system entrenches long-term inequities.

What Kind of Singapore Is Being Built?

The 99-year system raises uncomfortable questions about the nation’s direction —Is Singapore building a society where wealth is reset each century to prevent entrenched aristocracies? Or is it quietly eroding intergenerational stability for the masses while enabling a smal elite to accumulate power and property endlessly?

For young Singaporeans entering the housing market, the choices are stark: either stretch themselves financially for private property — increasingly unaffordable amid soaring prices — or accept the HDB lease knowing its endgame is state repossession.

This debate is not merely about property. It is about fairness, dignity, and the very notion of what it means to build a home. The government frames the leasehold as a “fair deal,” allowing affordability while ensuring land is recycled for future generations. But to the average citizen, it can feel like a never ending climb — working hard, buying a flat, only to have one’s children start from zero again.

And so, the question lingers: What type of Singapore is being built? A society of ever-resetting lives, bound by general apathy and complicity? Or one where citizens dare to demand more lasting security?

Ultimately, that question is for all Singaporeans to answer.

A stark reminder lingers — before Raffles arrived, Singapore was a thriving tropical port — its waters amongst the clearest and greenest, its people living modest yet joyful lives in kampongs where children could grow freely, and family planning was a hopeful, not burdensome, endeavour.

*This article is a commentary that reflects the author’s personal views and interpretation of Singapore’s housing policy. It is written to encourage civic awareness and public discourse, with sources provided for readers to explore further.

Author

News cycles today feel more dehumanising than ever. Netizen's deserve journalist's that believe in the power of narratives to inspire positive change — putting activism before profits and creating a blend of journalism that is raw, human, and alive.

Sign up for The Fineprint newsletters.

Stay up to date with curated collection of our top stories.